The desert inhabitants attacked and slayed one another with maces, knives and hunting weapons, probably fighting over scarce water and fertile land.

Around 1,000 B.C., some foragers decided to try farming in one of the driest spots on Earth, the Atacama Desert, which lies between the Andes Mountains and Pacific Ocean, in what’s now northern Chile. When farming began, lethal violence surged and remained high for centuries. The desert inhabitants attacked and slayed one another with maces, knives and hunting weapons, probably fighting over scarce water and fertile land.

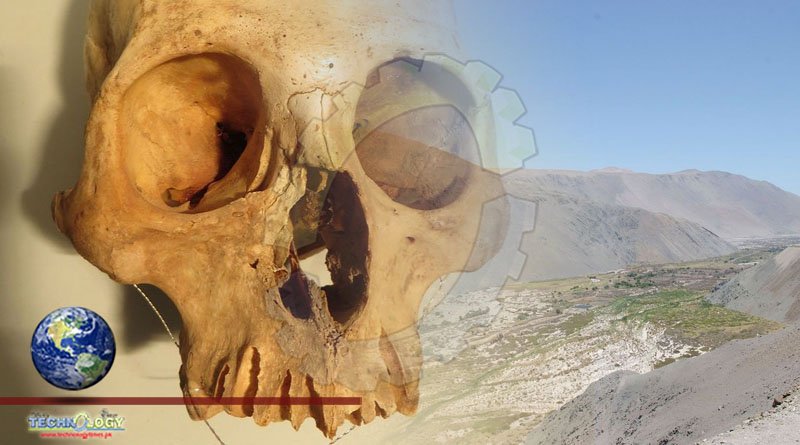

That’s according to a new analysis of human remains from graves between 3,000 and 1,400 years old, which included dozens of individuals with hair, flesh and organs still intact, due to the desert aridity. The victims suffered snapped ribs, broken collarbones, facial mutilation and puncture wounds in the lungs, groin and spine. At least half of the injuries look like they were fatal blows.

“The patterns and frequencies of the lethal trauma… is astonishing,” says Tiffany Tung, a Vanderbilt University archaeologist, who was not involved in the research.

The study, forthcoming next month in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, also laid out possible reasons for the bloody times, which take into account cultural traditions, climate change and scarce resources. According to Tung, who studies conflict in ancient South America, the results hold lessons for any society, including our own. “We can look to these other populations from different times and places to try to understand… these intense outbreaks of violence versus relative calm, relative peace,” she says. “What are the larger forces at play that are contributing to people wanting to harm, maim or actually kill another person?”

The Atacama is a prime place to investigate the triggers of deadly conflict because hundreds of well-preserved human remains have been excavated, spanning nearly 9,000 years of episodic violence and social change. For decades, Vivien Standen, lead author of the new study, has been examining these individuals, kept at her University of Tarapacá’s museum in Chile. “This collection was excavated many, many, many years ago. Today, we don’t excavate cemeteries anymore,” stresses Standen, a biological anthropologist.

The collection includes one of this year’s additions to UNESCO’s World Heritage List: the Chinchorro mummies, the world’s oldest mummies, which come from fisher-gatherers who lived along the coast between 10,000 and 4,000 years ago. For religious reasons, the ancient community deliberately made some of these mummies. But others were accidents: The sandy, salty desert staved off decomposition and baked the corpses into natural mummies. Previously, Standen’s and colleagues discovered that about one quarter of the adults from this period had suffered injuries, like broken bones and stabbings. However, most of those wounds had healed, meaning the person died from another cause sometime later. Though these coastal foragers brawled and received beatings, it seems they rarely fought to the death.

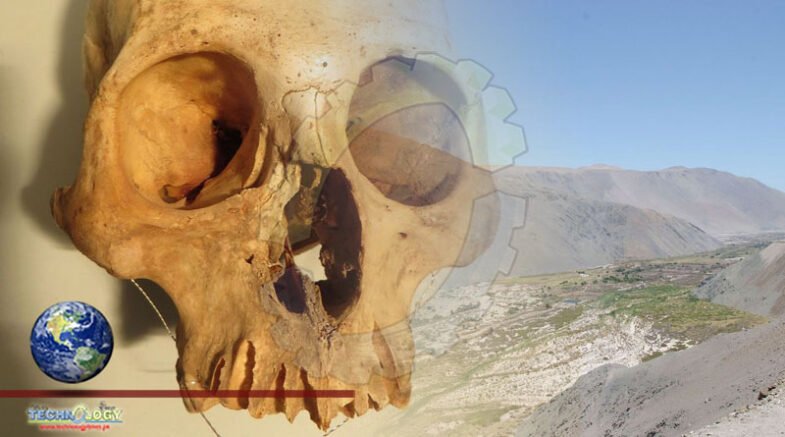

Standen wanted to know if this pattern held 1,000 years later, when farming appeared in the Atacama. At that time, seafood was becoming less dependable, due to climate changes affecting El Niño events. Some communities moved a day’s walk inland to oases and narrow river valleys fed by mountain snowmelt.

In that setting, “at the fringe of Atacama Desert… you have valley, green area. And then you have nothing. And then you have another small valley,” says Bernardo Arriaza, study coauthor and University of Tarapacá anthropologist. Along those skinny stretches of green, the ancient groups built villages, irrigated fields and planted corn, chili peppers and other crops, likely borrowed from non-desert farming villages to the north and east.

It was “kind of remarkable period in general, and there is so much change happening,” says University of California, Merced professor Christina Torres, who studies skeletal remains from Atacama sites, but was not involved in the new research. “It’s the first time we have so many people getting together, aggregating. So it’s not surprising that there would be conflict, and we would see it manifest in a variety of ways.”

To understand the rates and types of violence, Standen’s team returned to their museum collection to analyze 194 adult remains, dated between 1000 B.C. and 600 A.D. Chilean archaeologists excavated these skeletons in the 1970s and 80s from sites along a river valley about 10 miles from Chile’s border with Peru. Some of the cemeteries were monumental mounds made of shrubs, branches and earth. Others were mass graves, dug into the ground. By the time archaeologists exhumed the remains, most of the corpses had deteriorated to fragmentary bones. But, about 30 percent had surviving soft tissue, naturally mummified like the earlier Chinchorro individuals.

“The [preservation] of the bodies is excellent, so we can see the real people that lived in this environment,” Standen says.

Searching for markers of interpersonal violence, her team examined the loose bones and X-rayed the mummies. They discovered healed wounds, indicating victims survived attacks, as well as perimortem trauma, or injuries suffered around the time of death, which were probably the cause of death. Half the injuries appeared fatal, compared to just about 10 percent for the older coastal foragers.

With the onset of farming, “Everything is more lethal. Everything is more explosive,” says Arriaza.

Both males and females were battered. But notably, in another study, the team found few signs of trauma on children and infants, buried during the same period. “We don’t see too much child abuse,” adds Arriaza.

Beyond the overall patterns, specific injuries stood out. A healed cheekbone suggested a middle-aged male recovered from a bone-busting fist punch. Still sporting wavy chestnut hair, the face of a 20-something was likely bashed by a mace. Another skeleton exhibited a puncture wound in a vertebra, indicating the individual had been stabbed in the back. “You really get a sense of how intimate violence can be,” Tung says. It’s “not just broken bones. There’s a more human story to tell.”

She wonders, “Do they know that other person who enacted that violence against them?”

While the scientists cannot answer that definitively, they found clues, which suggest familiarity between perpetrators and victims. To determine whether the violence targeted locals or foreigners, the researchers drilled powder from the bones and teeth of 31 individuals with injuries and 38 individuals with no signs of trauma. At the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, geochemist Drew Coleman measured the samples’ strontium isotope ratios. This value varies depending on where someone lives and how much seafood they eat.

Based on these chemical signatures, the Atacama graves held no foreigners, say from Amazonia or the highland Andes. Regardless of whether or not they had injuries, everyone looked local—residents of the river valley or nearby coast. But, some of these locals had slightly higher strontium ratios, typical of seafood-rich diets, whereas others had lower values, suggesting they ate food from the valley. This could mean the conflicts were between traditional fishers and fledgling farmers.

The researchers found other evidence for violence from this period. Graves contained spear throwers, knives and other possible weapons. Rock art, engraved on valley cliffs, depicted stick figures, wearing headdresses and brandishing bows and darts. In a village along another river to the south, residents erected massive defensive walls and stocked sling stones behind it, probably as ammunitions to rain on raiders.

The archaeologists also sought to explain why local groups would fight to the death, just because some of them took up farming. They think a number of factors contributed. Considering the remains from the earlier times, residents of the region were prone to violence—probably spontaneous brawls, beatings and domestic abuse. But starting around 1,000 B.C., outside pressures sparked unrestrained, deadly assaults. Fishers faced less reliable catch, due to changes in the El Niño cycle. Fertile land and water for farming was always scarce on the fringes of Earth’s driest, hot desert. Facing climate change and famine, communities likely fought over water, land and food.

Farming was practiced in the narrow valleys of the Atacama Desert, where resources were scarce. (Courtesy of Vivien Standen)

Living there, “You’re gonna be very constrained in terms of where you can go, how much you can expand and use resources. You have the ocean on one hand. You have the desert on the other… That could have been one of the reasons why we see these some of the dramatic violence that my colleagues were able to document,” says José Capriles Flores, an archaeologist at Pennsylvania State University, who was not involved in the study, but has collaborated with the researchers before.

“We’re talking about these kind of brutal, marginal environments. People have to respond as best they can,” says Torres.

But just because events unfolded in a violent manner, does not mean that fate was inevitable for early farmers in the Atacama—or anyone facing harsh ecological conditions, Tung points out.

“It’s never just about the weather,” she says. “We as human beings, we make decisions about how to distribute resources. We have social norms and cultural practices.”

“Those are really powerful in shaping whether or not there’s going to be outbursts of violence, and also in who participates in the violence,” says Tung. She thinks these deaths, long ago in the Atacama Desert, are worth remembering amidst our current climate crisis—as global temperatures continue to rise, resources run scarce and communities face tough decisions.

Source Smithsonian Magazine