Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed “true migration” because they are irregular or in only one direction . Migration is marked by its annual seasonality. Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1800 of the world’s 10,000 bird species are long-distance migrants. Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the spring to breed in the temperate or Aortic summer and returning in the autumn to wintering grounds in warmer regions to the south. Of course, in the southern hemisphere the directions are reversed, but there is less land area in the far south to support long-distance migration.

There is more than one single reason for different birds to migrate, but it all comes down to survival. Journey for a bird to hundreds or thousands of miles between its breeding and non-breeding ranges is a difficult, perilous journey, one that not all birds survive. So why do birds migrate? What reasons send millions of birds into the skies every spring and fall? Without a reason to migrate, birds would have even more challenging lives than making these excruciating journeys. If no birds migrated, food supplies in their ranges would be rapidly depleted, and many chicks and adults would starve. Competition for nesting sites would be fierce, and predators would be attracted to the high concentrations of breeding birds and easy meals of nestlings. It is for those two reasons – food and breeding – that birds migrate, but those reasons are far more complicated than they seem.

For all birds, one of the principle driving forces behind migration is food scarcity. If all birds were to stay in the same tropical regions year-round, food would become scarce and breeding would be less successful. But as food sources are regenerating in the north each spring, millions of birds migrate to those areas to take advantage of the abundance. As the food supplies then dwindle in the fall, they return to replenished tropical regions. This pattern of migrating for a meal is true not only for geotropically migrants, but also short-range migratory birds that may move only short distances to pursue a food source. Bird irruptions are also the result of changes in the food supply, with greater irruptions occurring in years when food supplies are low for northern birds. That scarcity forces them to seek adequate food further south, well outside their typical range.

Over millennia, birds have evolved different migration patterns, timing and destinations to disperse around the world to breed. This helps birds take advantage of a wide variety of suitable conditions to raise their young, increasing the chances of healthy, viable offspring. The best breeding conditions can vary for every bird species, and may involve many factors. Specific food sources, habitats that provide adequate shelter and breeding colonies that offer greater protection than a single pair of bird parents are all important for breeding dispersal.

The other important reason to migrate is food, may be the key to a regular migration, but birds migrate for other reasons related to helping their offspring survive, including climate, birds have evolved different types of plumage to survive different climates, and changes in those climates can affect migration. Many birds leave the Arctic breeding grounds, for example, when temperatures begin to dip and they need more temperate habitat. Similarly, the hottest tropical regions can be a harsh environment for raising delicate chicks, and it is advantageous to lay eggs further north in cooler areas.

Another reason is habitats that have abundant food sources year-round also attract a greater number of predators that can threaten nests. Birds that migrate to different habitats can avoid that onslaught of predators, giving their young a better chance of reaching maturity. Many birds even migrate to specialized habitats that are nearly inaccessible to predators, such as coastal cliffs or rocky offshore islands. Any large group of birds crammed in one type of habitat is susceptible to parasites and diseases that can decimate thousands of birds in a short period of time. Diseases can and do occasionally devastate breeding colonies. Birds that disperse to different locations, however, have less chance of spreading a disease to their entire population, including their new offspring.

In the end, the reasons why birds migrates all come down to survival – not of the migrating birds themselves, but of the chicks they will raise. Finding richer food sources, seeking safer habitats and avoiding predators are all migration behaviours designed to ensure breeding success. Good migration allows birds to survive for another generation and allows birders the pleasure of witnessing another year’s migration.

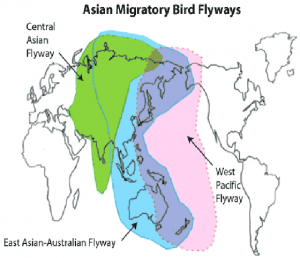

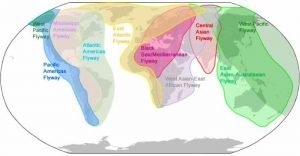

A flyway is a geographical region within which a single migratory species, a group of migratory species – or a distinct population of a given migratory species – completes all components of its annual cycle (breeding, moulting, staging, non-breeding etc.). For some species and groups of species these flyways are distinct ‘pathways’ linking a network of key sites. For other species/groups, flyways are more dispersed. More specifically, they defined a flyway as:“…the entire range of a migratory bird species (or groups of related species or distinct populations of a single species) through which it moves on an annual basis from the breeding grounds to non-breeding areas, including intermediate resting and feeding places as well as the area within which the birds migrate”.

Most migrations begin with the birds starting off in a broad front. Often, this front narrows into one or more preferred routes termed flyways. These routes typically follow mountain ranges or coastlines, sometimes rivers, and may take advantage of updrafts and other wind patterns or avoid geographical barriers such as large stretches of open water. The specific routes may be genetically programmed or learned to varying degrees. The routes taken on forward and return migration are often different. A common pattern in North America is clockwise migration, where birds flying North tend to be further West, and flying South tend to shift Eastwards.

Birds fly at varying altitudes during migration. An expedition to Mt. Everest found skeletons of northern pintail Anasacuta and black-tailed godwit Limosalimosa at 5,000 m (16,000 ft) on the Khumbu Glacier. Bar-headed geese Anserindicus have been recorded by GPS flying at up to 6,540 metres (21,460 ft) while crossing the Himalayas, at the same time engaging in the highest rates of climb to altitude for any bird. Anecdotal reports of them flying much higher have yet to be corroborated with any direct evidence. Seabirds fly low over water but gain altitude when crossing land, and the reverse pattern is seen in land birds. However, most bird migration is in the range of 150 to 600 m (490 to 1,970 ft). Bird strike aviation records show most collisions occur below 600 m (2,000 ft) and almost none above 1,800 m (5,900 ft).

Bird migration is not limited to birds that can fly. Most species of penguin (Spheniscidae) migrate by swimming. These routes can cover over 1,000 km (620 mi). Dusky Dendragapus obscure perform altitudinal migration mostly by walking. Emus Dromaiusnovaehollandiaein Australia have been observed to undertake long-distance movements on foot during droughts.

Pakistan lies at a crossroads for bird migration, as a result of its deliberate geographical location. The Indus basin is one of the world’s great migratory flyways and is the principal route followed by many bird species that breed extra limitedly and winter in Pakistan or in other regions of the Indian subcontinent. This includes a wide variety of ducks and waders, raptors, and passerines such as warblers, pipits and buntings. Some species including Common and Demoiselle cranes, snipe and pelican enter via the Kurram Agency of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan.

Pakistan has the large number of guest birds from Siberia and Central Asian States every year. The birds from North spend winters in different wetlands of Pakistan, which are distributed almost throughout the country, from the high Himalayas to the coastal areas and mudflats of the Indus delta. After winters they go back to their native habitats. This famous route from Siberia/Central Asia to various destinations in Pakistan over Karakorum, Hindu Kush, and Suleiman Ranges along Indus River down to the delta is known as Central Asian – South Asian Migratory Bird Flyway.

Endowed with a remarkable ecology, Pakistan spans several of the world’s ecological zones and is spread over broad latitude. The rich Indus delta and the highlands in Pakistan are a great attraction for the guest birds. The birds’ arrival start from the middle of August and January is the peak time and by March they flying back home. These periods may vary depending upon weather conditions in Siberia and Pakistan.

The strange phenomenon of birds’ migration is centuries old. Homer and Aristotle are said to have been observing the event of birds’ migration. They could at best call disappearing of birds from an area as hibernation. Their hypothesis has not stood the empirical observations of today. American Department of Fisheries and Wildlife and Canadian Department of Wildlife in1920 jointly carried out the first scientific study by tying Aluminium rings with the feet of birds and tracking them with radio.

Useful work in this field is continuously being under taken ever since in almost every country interested in conservation of natural life including Pakistan. These days the bird watching, ringing and tracking is carried out with the help of modern and sophisticated equipment like radio, radar and satellites.

The Central Asian Flyway is important due to the diverse species and large number of birds that take this itinerary: different species of water birds arrived and select their suitable habitat according to their feeding and resting preference. As per an estimate based on regular counts at different Pakistani wetlands, between 700,000 and 1,200,000 birds arrive in Pakistan during each migratory season. Now these days bird watching has become an increasingly popular pursuit in Pakistan, more and more people have started taking break and are seen on rendezvous with birds.

Different birds face different threats along their journeys, but all birds have to endure some risks as they migrate. The most common and most deadly threats to migrating birds include. Birds fly hundreds of miles during migration, often covering large distances without food and rest. Exhaustion can make birds less wary of potential threats, and tired birds are more apt to collide with obstacles or falter in flight. This is especially true if their flight path passes through storms or unfavourable wind patterns, or if birds are migrating later in the season and must cover more distance each day to reach their destination.

Inadequate food supplies cause starvation among migrating birds every year. This may be caused by habitat destruction that effectively strands migrating birds without food along their route, or it can be due to greater feeding competition among large flocks of migratory birds. Tens of thousands of migrating birds collide with obstacles in mid-flight during both spring and fall migrations, and the majority of these collisions cause fatal injuries. Even if the birds are not killed on impact, stunned birds are more susceptible to predators. The most common obstacles that are hazardous to migrating birds include tall glass buildings, electrical wires and poles, wind turbines and similar structures.

Predators kill hundreds of thousands of birds each year, and during migration, migrating birds may be unaware of local predators at stopovers during their journey. Outdoor cats and feral cats are the most common predators that threaten migrating birds, but even wild predators can be a deadly hazard. When migrating birds gather in large flocks, a disease outbreak can be devastating. This can be even more detrimental when surviving birds carry the illness to either breeding grounds or densely populated winter ranges. In those large flocks, more birds may become infected and the overall population can be decimated. Pollution such as lead poisoning or oil spills is not only harmful to locally affected birds, but to migratory birds as well. Polluted habitats provide less food, and birds that ingest toxins during migration may continue to suffer from the poisonous effects longer after leaving the area. Furthermore, heavy pollution will reduce available food supplies and suitable habitat, making it more difficult for birds to complete their migration successfully. Hurricanes, blizzards, wildfires and other natural disasters can destroy crucial stopover and rest sites as well as destroying food sources birds need to refuel along their journeys. Birds that are caught in these disasters can suffer other effects that cause injury, debilitation or death, such as singed feathers in a wildfire or freezing in an early or late blizzard.

Many hunting seasons coincide with migration periods, making this perilous time even more threatening for birds. Illegal hunting and poaching are also a threat at this time. Even legitimate, experienced hunters may make mistakes and inadvertently shoot protected birds that they have misidentified in flight.

A bird’s own inexperience with migration can be a great threat to its success and survival. Many juvenile birds make these long journeys without guidance from adults. They may not be able to complete the trip if they are unsuccessful in finding adequate food or if they stray too far from the typical migration route.

The first step in helping birds migrate successfully is to understand the threats they face along the way. Birders who want to help migrating birds can minimize those threats by creating bird-friendly landscaping and preserving natural habitats for birds to rest and refuel during migration. This includes choosing native plants and providing water to birds as well as offering good food both naturally and through supplemental feeders. Feeding birds year-round and choosing healthy, nutritious foods such as suet, black-oil sunflower seeds, fruit, nuts and nectar to offer. These foods provide high amounts of fat and sugar to help birds have plenty of energy during migration. Keeping bird feeders clean and fresh to avoid spreading diseases that could infect migrating birds and thus spread to migratory flocks.

Minimizing or avoiding pesticide use during bird migration season and taking care to dispose of oil, lead and other toxic materials safely and responsibly so there is no environmental contamination that can affect birds. If a spill occurs, participating in clean-up efforts can help protect both local and migratory birds.

Supporting strong enforcement of local hunting laws and measures to prevent poaching or illegal hunting activities.

Sharing your love of birds with friends and family members to introduce them to this rewarding hobby. This helps raise awareness of birds in every season and encourages more people to enjoy migration and protect migrating birds.

Migration is a natural part of many birds’ lives, but it is one fraught with danger. By understanding the threats migrating birds face, it is possible for every birder to take steps to help their feathered friends complete these seasonal journeys safely.

This article is written in connection with International Bird Migrator Day. International Migratory Bird Day is a conservation initiative that brings awareness on conserving migratory birds and their habitats throughout the Western Hemisphere.

The author Dr. Syed Javed Khurshid is a Science Communication Expert; Dr. Syed Najam Khurshid is a former Regional Coordinator RAMSAR. The Ramsar Convention is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands. It is also known as the Convention on Wetlands. It is named after the city of Ramsar in Iran, where the Convention was signed in 1971.