Rabies has a significant global impact, with an estimated 30,000 to 70,000 deaths annually, primarily affecting less developed countries.

Rabies is a preventable viral disease primarily transmitted through the bite of a rabid animal. This viral infection affects the central nervous system of mammals, leading to severe neurological symptoms and, ultimately, death.

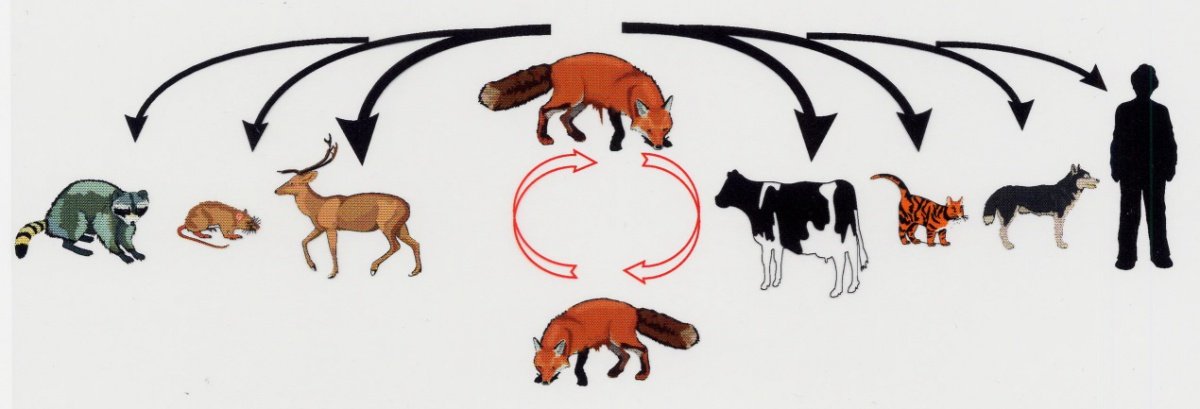

It is a lethal disease spread to humans through contact with the saliva of infected animals, often via bites. The primary carriers of the rabies virus in the United States include bats, coyotes, foxes, raccoons, and skunks. In developing countries, rabies is commonly transmitted by stray dogs. While rabies is a fatal disease, it is also preventable. Effective prevention involves prompt medical intervention for individuals bitten or scratched by rabid animals.

Epidemiology

Rabies has a significant global impact, with an estimated 30,000 to 70,000 deaths annually, primarily affecting less developed countries. In the United States, human cases of rabies are relatively rare, a testament to the success of post-exposure prophylaxis and prevention programs.

In developed countries, domesticated animals contribute to about 10% of rabies transmission cases, while wild animals, particularly skunks, raccoons, foxes, and bats, account for the majority of cases. Rabies can potentially be transmitted by any mammal, making regional knowledge of rabies carriers essential for determining prophylactic needs.

Lyssaviruses and Their Hosts

The Lyssavirus genus, which includes the rabies virus (RABV), is characterized by extensive diversity. Bats, the only mammals capable of true flight, often serve as the primary reservoir hosts for many Lyssavirus species.

While reservoir hosts for certain viruses are well-documented, such as the European bat lyssaviruses (EBLVs), limited information is available for others due to the scarcity of isolates. Enhanced surveillance and sequencing technologies continue to refine the taxonomy of this genus.

Risk Factors

Several factors can increase the risk of rabies exposure, including:

- Travel or residence in developing countries where rabies is more prevalent

- Engaging in activities that entail contact with wild animals, such as exploring caves inhabited by bats or camping without proper precautions

- Occupations involving interaction with potentially rabid animals, such as veterinary work or laboratory research with the rabies virus.

- Wounds to the head or neck, which can expedite the virus’s travel to the brain, potentially increasing the risk of infection.

Transmission

Rabies virus transmission occurs through direct contact with an infected animal’s saliva or brain/nervous system tissue, typically through broken skin or mucous membranes in the eyes, nose, or mouth.

Path of the Rabies Virus

- A rabid animal bites one of the animals.

- The rabies virus from the infected saliva enters the wound.

- The virus travels along nerves to the spinal cord and brain, a process lasting 3 to 12 weeks without visible signs of illness.

- Once it reaches the brain, the virus multiplies rapidly and moves to the salivary glands, leading to observable symptoms.

- The infected animal typically succumbs to the disease within seven days of exhibiting symptoms.

Its transmission from animals to humans is shown in Figure 1.

Signs and symptoms

The incubation period for rabies, the time between exposure and symptom onset, can vary significantly. The location of the exposure site, the specific rabies virus involved, and any existing immunity all play a role.

Initial symptoms may mimic flu-like symptoms, such as weakness, fever, and headache, accompanied by discomfort or itching at the bite site. These symptoms may last for days before progressing to more severe manifestations, including cerebral dysfunction, anxiety, confusion, and agitation.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing rabies disease at the time of an animal bite is challenging, as the virus may not be immediately detectable. Clinical tests to detect the rabies virus might need to be repeated later for confirmation.

If there’s a potential rabies exposure, treatment should be administered promptly to prevent viral infection. Laboratory identification of positive rabies cases plays a crucial role in epidemiological surveillance and the development of effective rabies control programs.

Muhammad Hussain, Ahram Hussain, and Muhammad Hamza from the University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore subcampus, Jhang.