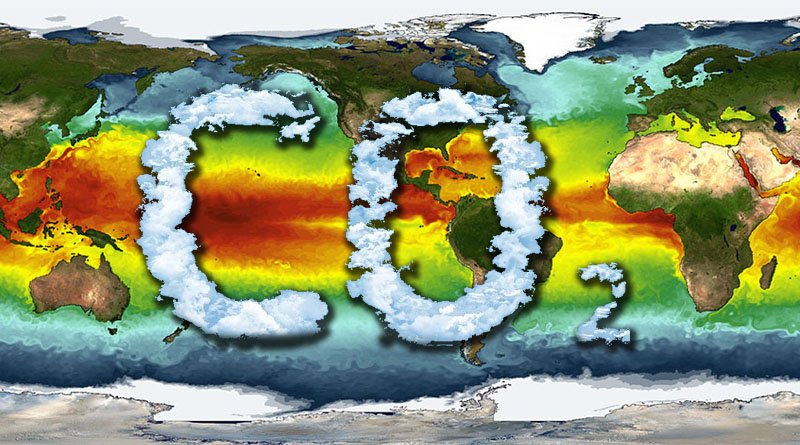

The UN has highlighted the need for CO2 removal to achieve net zero emissions and limit warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels.

Viktoria Oseyko and her father Nick were forced to flee Ukraine in February last year due to Russia’s invasion. Ukraine soon regained control and Viktoria and her team have since completed a pilot trial of their machine that can capture CO2 from the air and pipe it into greenhouses. This helps farmers grow crops. Carbominer is one of many startups in Europe racing to develop tech to capture carbon dioxide, which accounts for 66% of global warming.

The UN has highlighted the need for CO2 removal to achieve net zero emissions and limit warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels. This is due to committed warming, which is the future warming caused by the greenhouse gases we have already emitted. The 10-strong team at Carbominer is developing machines that can capture 46 tonnes of CO2 annually by the end of the year.

Although this is a relatively small-scale project, the company, which has so far raised $900,000 (€822,000) in funding, anticipates being able to offer captured CO2 to agricultural clients at a reasonably low cost.

Oseyko says, “We’re going to set up the machine on site and then bill per usage of CO2.” The inability to currently import materials into the country, she continues, is one of the difficulties faced by Carbominer and many other Ukrainian businesses.

Additionally, male staff members are currently prohibited from leaving Ukraine due to martial law, which makes it challenging to network with the sector and visit potential clients. To counteract this, the company intends to set up shop in Oseyko’s home country of Poland this year.

The system created by Carbominer consists of two connected machines. The other machine uses electrochemistry to release the CO2 when necessary, and the first machine uses a large fan to draw air towards a sorbent, which captures the CO2.

However, one of the main issues with direct air capture systems is the need to move air around to access the CO2 contained therein, which consumes energy.

Carbominer’s system ceases to be carbon negative, according to Oseyko, when fossil fuel-based electricity is used to power it. However, the company only plans to use renewable energy. The Soletair Power team in Finland has been considering ways to circumvent the energy consumption issue.

Soletair Power’s carbon capture tech essentially piggybacks on existing ventilation systems in buildings, transporting indoor air rich in CO2 breathed out by occupants. The amount of CO2 captured depends on the volume of air moved in each case, but systems already installed by the firm capture on the order of tens of kilos of CO2 per day.

Soletair Power has installed its technology in Vaasa, Finland, where the trapped CO2 is used in the manufacture of concrete.

Dawid Hanak at Cranfield University believes this technology is valid and scalable. Laakso has already installed systems in Finland and Germany and will install another this summer. Real estate companies are promising to be carbon net zero by 2028 and are turning to Laakso for help.

Depending on the installation, a large system can currently remove CO2 for between €500 and €1,000 per tonne. Many businesses want to eventually reduce the price of removal to $100 (€91) per ton or less so that CO2 capture is feasible at the scales needed to achieve net zero.

There are advantages and disadvantages to carbon capture tech. There are simpler ways to lessen humanity’s impact on the climate, according to Stuart Haszeldine at the University of Edinburgh. “Getting more value out of the same energy is actually the simplest way to address the climate issue,” he claims. For instance, insulate buildings to reduce the energy needed to heat them.

But according to Haszeldine, who contends that businesses that can lower their overall CO2 output will have an advantage in terms of revenue and perception, reducing one’s carbon footprint will grow in commercial appeal.

Additionally, direct air capture aids in addressing CO2 emitters like farming that are widely dispersed and therefore challenging to control. At least you can remove CO2 from the atmosphere later if you can’t reliably capture it at the source.

Silicate is a startup in Ireland that has developed a way to treat agricultural land to draw carbon out of the air and into the ground.

It employs ten people and has raised funding through grants, including $100,000 as a winner of the Thrive / Shell Climate-Smart Agriculture Challenge. The process involves crushing unwanted or waste concrete into a powdery material, which is spread over a field every four years to maintain a high soil pH.

Silicate’s approach to de-acidifying soil involves reacting concrete with carbonic acid in the soil, removing CO2 from the air. The substances formed by this process, bicarbonate and calcite, should store carbon for thousands of years.

The firm aims to achieve removal rates of two tonnes of CO2 per hectare for every 10 tonnes of crushed concrete applied to such an area. The cost of the process is likely to fall below the $100 per ton price point.

Although the tech for direct air carbon capture is still in its infancy, investments in carbon capture and storage have increased by more than a factor of two over the past year, and they are expected to reach an all-time high of nearly €6 billion in 2022.

These technologies will probably play a noticeably bigger role in the upcoming years due to the abundance of startups working in this field and the increasing urgency of achieving net zero globally.