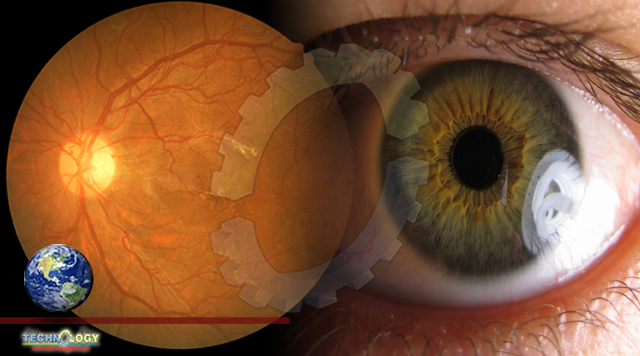

A new form of gene therapy may help prevent vision loss caused by diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma, according to a study published Thursday by the journal Cell.

By Brian P. Dunleavy

Mice injected with genes intended to boost production of a key enzyme involved in sending images to the brain were protected against progressive vision loss or impairment in multiple disease and injury models, the researchers said.

The enzyme, called CaMKII, helps bolster retinal ganglion cells, which process visual information by sending images to the brain. They can degenerate as a result of retinal injury and retinal disease.

“Neuroprotective strategies to save vulnerable retinal ganglion cells are desperately needed for vision preservation,” study co-author Bo Chen said in a press release.

“We uncovered evidence for the first time that CaMKII … could be a desirable therapeutic target for vision preservation in conditions that damage the axons and somas of retinal ganglion cells,” said Chen, an associate professor of ophthalmology and neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible visual impairment worldwide, affecting 76 million people, according to the World Health Organization.

Many people with the disease progress to blindness despite aggressive treatment to reduce the pressure in their eyes that causes it, Chen and his colleagues said.

Currently, no cures exist for diseases such as glaucoma that damage the retina.

The challenge in repairing vision loss from glaucoma and other retinal diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy, is that the long nerve fibers known as axons do not regenerate on their own, researchers said.

Axons enable retinal ganglion cells to process visual information by converting light that enters the eye into a signal transmitted to the brain.

For this study, the Mount Sinai researchers tested the enzyme CaMKII as a therapeutic target for a wide range of injuries and diseases in mice, including optic nerve damage and glaucoma with both high and normal intraocular, or eye, pressure.

In the mice used in the study, CaMKII helped preserve retinal ganglion cells across many of these injuries and diseases, the researchers said.

Mice who had genes designed to boost production of CaMKII injected directly into their eyes were protected from progressive vision loss caused by injuries and diseases that damaged the retinal ganglion cells.

The gene therapy approach is intended to introduce a more active type of CaMKII — with a mutated amino acid — that was transferred to the targeted retinal ganglion cells using a non-harmful virus to carry it, according to the researchers.

The approach has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and is commonly used in the growing field of gene therapy, the researchers said.

They plan to test the method in larger animal models, which may pave the way for starting clinical trials in humans.

Mount Sinai has filed patent applications for the technology through Mount Sinai Innovation Partners, the commercialization arm of the health system, which is in active discussions with multiple companies to help advance this treatment, the hospital said.

“Our research showed that CaMKII could indeed be a valuable therapeutic target to save retinal ganglion cells and preserve vision in treating potentially blinding diseases like glaucoma,” Chen said.

“The fact that manipulation of CaMKII would involve a one-time transfer of a single-gene adds to its vast potential to treat serious retinal conditions in humans,” he said.

Originally published at Upi