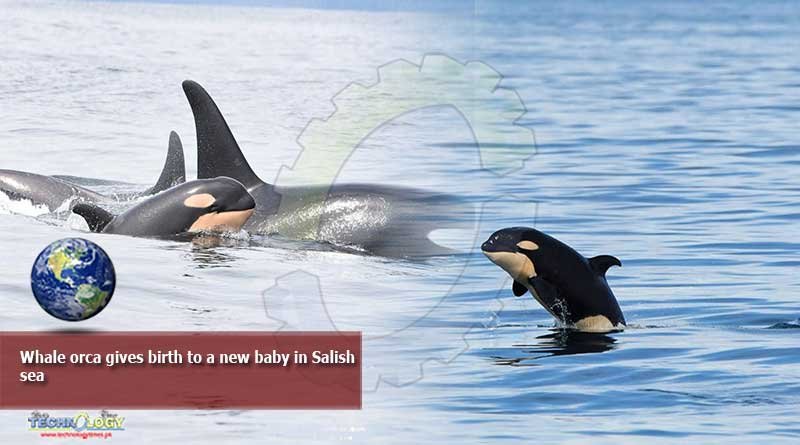

The orca that gained global attention for carrying her dead newborn on her nose for 17 days in the Salish Sea has given birth again.

The orca that gained global attention for carrying her dead newborn on her nose for 17 days in the Salish Sea has given birth again. She and her new baby were spotted swimming together on Saturday.

A whale watching boat tipped off researchers that they’d seen a newborn southern resident orca calf south of San Juan Island on Saturday.

“I definitely cried,” whale watch captain Sarah McCullagh with San Juan Safaris said in a press release from the Pacific Whale Watch Association.

McCullagh was the first person to see the new whale, its head still smaller than its mother’s dorsal fin.

She radioed the Center for Whale Research’s boat to get a better look—only researchers with federal permits are allowed to approach whales up close.

The researchers confirmed a new calf swimming beside its international celebrity mom, dubbed “J35” by scientists and “Tahlequah” by The Whale Museum in Friday Harbor.

“I was obviously elated, so excited for J35 after the incredible loss she suffered a couple of years ago, but also for the southern resident community as a whole,” McCullagh said.

“J35’s new calf appeared healthy and precocious, swimming vigorously alongside its mother in its second day of free-swimming life,” the Center for Whale Research stated in a press release.

The center also announced Sunday that another member of J pod, J 41, is pregnant, making a total of four known pregnancies this summer among the endangered orcas.

While the mammal-hunting transient orcas have been increasing in number, the fish-eating southern residents now number 73 individuals, their lowest since 1976.

J35 lugged her dead baby’s body for close to 1,000 miles in July and August 2018 in what was dubbed a “Tour of Grief.”

With orca pregnancies lasting 18 months, her new baby would have been conceived about six months later.

After the first August on record in which none of the southern residents were spotted in their home waters, near southern Vancouver Island, the orcas’ J pod returned to the Salish Sea Sept. 1.

Most or all of K pod and L pod followed three days later, with close to the entire population assembling in the sheltered waters between Washington and British Columbia for the first time in 2020.

“We saw a lot of surface activity as well as socializing behavior with breaches happening all scattered throughout,” Andrea Mendez-Bye with Oceans Initiative said. “We even got to hear vocalizations above the surface, which is incredible because we’re on land.”

Mendez-Bye is a research assistant on a team studying the orcas’ behavior with high-powered lenses from coastal bluffs on the west side of San Juan Island.

Despite squinting into the late-afternoon sun, they saw one female orca “logging” in the water a few miles offshore.

“They call it logging because it looks like a log in the water,” Mendez-Bye explained. “It chills at the surface.”

Mendez-Bye said the behavior is often seen in nursing mothers.

“She was perfectly in the glare of course, so we couldn’t take any photos, but we did see a tiny head pop up that was smaller than a pectoral fin,” she said.

The orca floated at the surface, apparently alone, for some time, then other orcas circled around it.

Mendez-Bye said, with the glare and the distance, the Oceans Initiative team couldn’t be certain which orcas they were seeing.

Even making it this far, the newest orca, known as J57, has beaten some odds. Most pregnancies among the endangered southern resident killer whales end in miscarriage, and close to half of the newborns die before their first birthday.

Firstborn orcas often have a harder time than later offspring, since their mothers’ milk can contain many years’ buildup of toxic pollutants.

J35 also has a 10-year-old son, J47, seen swimming with his mother and baby sister Saturday.

While researchers and whale watchers alike view this birth as a joyous occasion, many more births would be needed for the southern residents to bounce back from the brink of extinction.

“We should have six or eight females giving birth every year,” Giles said. Giles said the lack of Chinook salmon to eat drives the lack of successful pregnancies among the endangered orcas.

After gathering to human observers’ delight on Saturday, the southern resident killer whales were not seen on Sunday. They are presumed to have headed out to the open Pacific again.

The article is originally published at kuow.