A research team led by Northwestern University has designed and synthesized new materials with ultrahigh porosity and surface area for the storage of hydrogen and methane for fuel cell-powered vehicles. These gases are attractive clean energy alternatives to carbon dioxide-producing fossil fuels.

The designer materials, a type of a metal-organic framework (MOF), can store significantly more hydrogen and methane than conventional adsorbent materials at much safer pressures and at much lower costs.

“We’ve developed a better onboard storage method for hydrogen and methane gas for next-generation clean energy vehicles,” said Omar K. Farha, who led the research. “To do this, we used chemical principles to design porous materials with precise atomic arrangement, thereby achieving ultrahigh porosity.”

Adsorbents are porous solids which bind liquid or gaseous molecules to their surface. Thanks to its nanoscopic pores, a one-gram sample of the Northwestern material (with a volume of six M&Ms) has a surface area that would cover 1.3 football fields.

The new materials also could be a breakthrough for the gas storage industry at large, Farha said, because many industries and applications require the use of compressed gases such as oxygen, hydrogen, methane and others.

Farha is an associate professor of chemistry in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. He also is a member of Northwestern’s International Institute for Nanotechnology.

The study, combining experiment and molecular simulation, will be published on April 17 by the journal Science.

Farha is the lead and corresponding author. Zhijie Chen, a postdoctoral fellow in Farha’s group, is co-first author. Penghao Li, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Sir Fraser Stoddart, Board of Trustees Professor of Chemistry at Northwestern, also is a co-first author. Stoddart is an author on the paper.

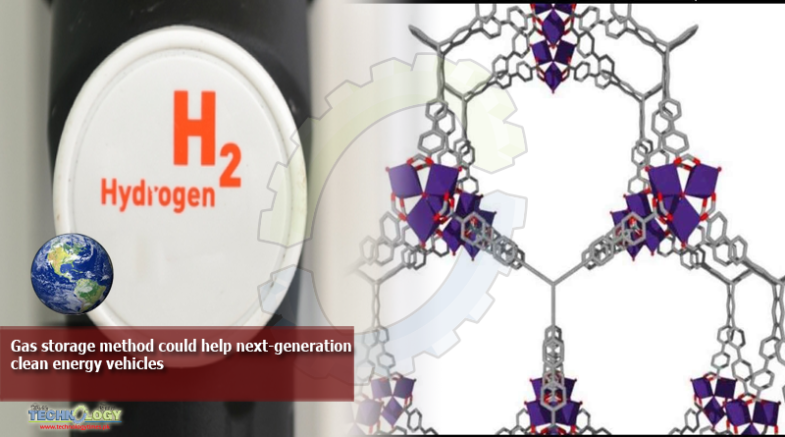

The ultraporous MOFs, named NU-1501, are built from organic molecules and metal ions or clusters which self-assemble to form multidimensional, highly crystalline, porous frameworks. To picture the structure of a MOF, Farha said, envision a set of Tinkertoys in which the metal ions or clusters are the circular or square nodes and the organic molecules are the rods holding the nodes together.

Hydrogen- and methane-powered vehicles currently require high-pressure compression to operate. The pressure of a hydrogen tank is 300 times greater than the pressure in car tires. Because of hydrogen’s low density, it is expensive to accomplish this pressure, and it also can be unsafe because the gas is highly flammable.

Developing new adsorbent materials that can store hydrogen and methane gas onboard vehicles at much lower pressures can help scientists and engineers reach U.S. Department of Energy targets for developing the next generation of clean energy automobiles.

To meet these goals, both the size and weight of the onboard fuel tank need to be optimized. The highly porous materials in this study balance both the volumetric (size) and gravimetric (mass) deliverable capacities of hydrogen and methane, bringing researchers one step closer to attaining these targets.

“We can store tremendous amounts of hydrogen and methane within the pores of the MOFs and deliver them to the engine of the vehicle at lower pressures than needed for current fuel cell vehicles,” Farha said.

The Northwestern researchers conceived the idea of their MOFs and, in collaboration with computational modelers at the Colorado School of Mines, confirmed that this class of materials is very intriguing. Farha and his team then designed, synthesized and characterized the materials. They also collaborated with scientists at the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) to conduct high-pressure gas sorption experiments.

The title of the paper is “Balancing volumetric and gravimetric uptake in highly porous materials for clean energy.”

Originally Publish at: https://phys.org/