The hemorrhagic fever virus known as Marburg can cause the body’s organs to shut down. Although symptoms can vary, they typically begin with a headache and fever.

Marburg, an infectious virus with high mortality rates and the potential to become an epidemic, has recently been reported in a second nation of Africa. The news has increased the urgency of ongoing Marburg vaccine development efforts and raised concerns among public health officials that the planet’s changing climate may be causing outbreaks.

Bats assemble in the Bat Cave in Queen Elizabeth National Park on August 24, 2018. To learn more about the bats’ flight patterns and how they spread the Marburg virus to humans, scientists fitted some of them with GPS devices. There are about 50,000 bats living in the cave.

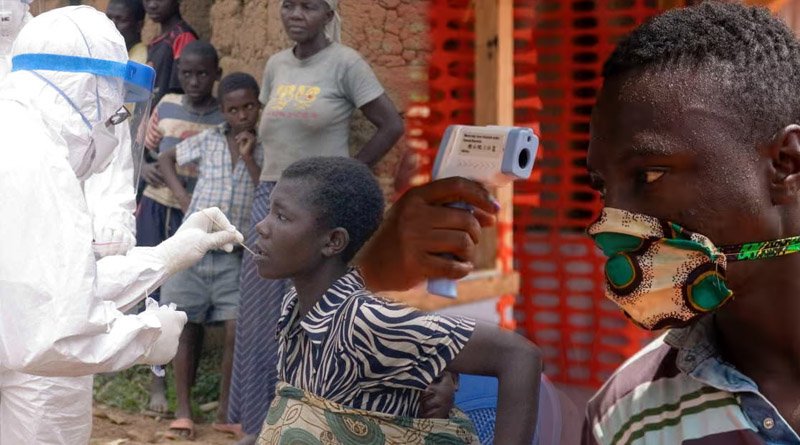

Equatorial Guinea of Africa reported the first outbreak of Marburg Virus of the year in February, but WHO was concerned that the nation was undercounting those cases. Since the start of the pandemic, 13 cases have been confirmed in Equatorial Guinea, according to Reuters on Wednesday.

The case count update came the same day that WHO asked Equatorial Guinea to be open about how many cases the nation had because local staff suspected there might be more cases. Additionally, 20 likely cases—all of which were fatal—have been reported from Equatorial Guinea.

Tanzania is also reporting a Marburg outbreak and has confirmed eight cases, including five deaths in the northwest Kagera region, according to WHO. Tanzania is located about 1800 miles away and on a different continent.

The hemorrhagic fever virus known as Marburg can cause the body’s organs to shut down. Although symptoms can vary, they typically begin with a headache and fever. The fruit bat, which is frequently found in caves, is thought to be the host animal. Bats can directly infect people, or they can infect monkeys and pigs, which then infect humans.

Direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of an infected person as well as through any objects, such as bed sheets, that become contaminated with the infected fluids are the two main ways that Marburg is transmitted.

As with Ebola, burial rituals have occasionally been a way for people to get sick if they come in contact with someone who died from the virus.

Diagnosis of Marburg Virus is difficult in poor countries due to a lack of labs to test disease samples, and the outbreak in two parts of Africa could be linked to climate change.

Dr. Lee Hampton, an epidemiologist with GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, believes that climate change could lead to host animals for the Marburg virus moving to areas they have not been before, creating outbreaks where they have never been before.

WHO’s Director General General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus spoke about the effects of climate change on disease at a press conference this week. He noted that the outbreaks of Marburg virus disease are a reminder that we must protect the health of animals and our planet.

WHO is working with the Food and Agriculture Organization, World Organisation for Animal Health and the UN Environment Programme to address the issue.

The organisations spoke at a meeting held last week at the WHO’s headquarters and urged nations to “[strengthen] the policies, strategies, plans, evidence, investment, and workforce needed to properly address the threats that arise from our relationship with animals and the environment.”

The WHO convened a meeting of experts to discuss possible vaccines and treatments for the virus. On Wednesday, the WHO Director General announced the agency is working to begin trials of vaccines and therapeutics as soon as possible.

The next step is to convene a working group to develop the legal framework for clinical trials. Gavi’s Hampton says working quickly to develop a vaccine is critical because every outbreak is a chance for the virus to spread out of control.

The WHO is coordinating scientists to monitor the virus in populations of fruit bats, bat faeces and aerosols, and human populations, including hospital data, bushmeat diets, and the mobility of humans and animals.

Oladele A. Ogunseitan, Ph.D., a professor of population health and disease prevention at the University of California, Irvine, says this multi-pronged approach has been used successfully with COVID-19 with the monitoring of the virus in urban wastewater, rats, and deer populations to predict trends.

However, coordination has been sporadic and not as effective as it would have been if planned from the get go.

Marburg was first identified in 1967 among lab workers in Marburg, Germany, and Belgrade, Serbia, who were exposed to the virus during research with monkeys or tissue samples of the monkeys originally from Uganda. It is similar to many other illnesses and can spread before it is identified and isolated.

The first case in the Equatorial Guinea outbreak may have emerged in early January of this year, but it only prompted alarm in early February when a health worker saw patients with severe symptoms associated with Marburg, including bloody diarrhoea and blood in vomit.

Marburg virus can be difficult to diagnose early on, with symptoms ranging from fever, chills, headache, and body aches to jaundice, an inflamed pancreas, severe weight loss, delirium, massive internal bleeding, shock, and multi-organ failure.

The fatality rate varies widely, but the WHO puts it around 50%. Public health experts have several tactics to try to prevent outbreaks, such as developing a workforce capable of interpreting early warning systems and collaborating to prevent pandemics.