FOUR YEARS AGO, organizers created the international AI Smart-City Challenge to spur the development of artificial intelligence for real-world scenarios like counting cars traveling through intersections or spotting accidents on freeways.

In the first years, teams representing American companies or universities took top spots in the competition. Last year, Chinese companies won three out of four competitions.

Last week, Chinese tech giants Alibaba and Baidu swept the AI City Challenge, beating competitors from nearly 40 nations. Chinese companies or universities took first and second place in all five categories. TikTok creator ByteDance took second place in a competition to identify car accidents or stalled vehicles from freeway videofeeds.

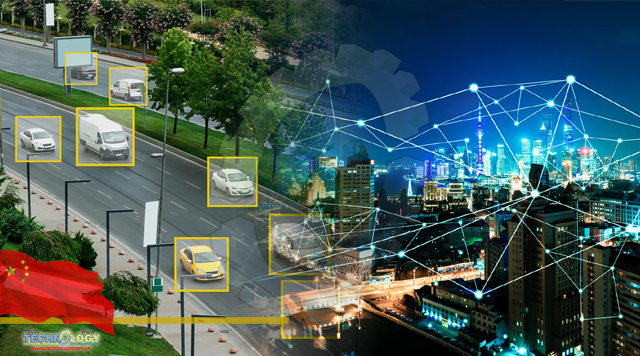

The results reflect years of investment by the Chinese government in smart cities. Hundreds of Chinese cities have pilot programs, and by some estimates, China has half of the world’s smart cities.

The spread of edge computing, cameras, and sensors using 5G wireless connections is expected to accelerate use of smart-city and surveillance technology.

The tech displayed in these competitions can be useful to city planners, but it also can facilitate invasive surveillance. Counting the number of cars on the road helps civic engineers understand the resources required to support roads and bridges, but tracking a vehicle across multiple live camera feeds is a powerful form of surveillance.

One of the competitions in the AI City Challenge asked participants to identify cars in videofeeds; for the first time this year, the descriptions were in ordinary language, such as “a blue Jeep goes straight down a winding road behind a red pickup truck.”

The competition comes at a time of increased tech nationalism and tension between the US and China, and growing concern over the powers of AI. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2019 called China “a major driver of AI surveillance worldwide.” The group said China and the US were the two leading exporters of the technology.

Last month, the Biden administration expanded a blacklist started by the Trump administration to nearly 60 Chinese companies barred from receiving investment from US financiers.

Also in recent weeks, the US Senate passed the Competition and Innovation Act, providing billions in investment for chips, AI, and supply chain reliability. It also calls for investment in smart cities, including expanding a smart-city partnership with southeast Asian nations (excluding China).

China’s domination of the smart-city challenge may come with an asterisk. John Garofolo, a US government official involved in the competition, says he noticed fewer US teams this year. Organizers say they don’t track participants by country.

Stan Caldwell is executive director of Mobility21, a project at Carnegie Mellon University assisting smart-city development in Pittsburgh. Caldwell laments that China invests twice as much as the US in research and development as a share of GDP, which he calls key to staying competitive in areas of emerging technology.

He says AI researchers in the US can also compete for government grants like the National Science Foundation’s Civic Innovation Challenge or the Department of Transportation’s Smart City Challenge.

A report released last month found that a $50 million DOT grant to the city of Columbus, Ohio, never quite delivered on the promise of building the smart city of the future.

“We want the technologies to develop, because we want to improve safety and efficiency and sustainability. But selfishly, we also want this technology to develop here and improve our economy,” Caldwell says.

Spokespeople for Alibaba and Baidu declined to comment, but advances from smart-city challenges can help fuel commercial offerings for both companies.

Alibaba’s City Brain tracks more than 1,000 traffic lights in the company’s hometown of Hangzhou, a city of 10 million people. A pilot program found that City Brain reduced congestion and helped clear the way for emergency responders.

Chinese companies have done well in other US-sponsored assessments of surveillance technology. Chinese firms including Alibaba-backed Megvii performed well on facial-recognition accuracy tests from the National Institute for Standards and Technology.

The US is also encouraging AI researchers to develop smart-city surveillance technology with ASAPS, a competition to make AI that helps emergency operators predict when they should dispatch an ambulance, fire engine, or police.

In that competition, teams analyze a combination of text, photo, and video data as well as mock Facebook and Twitter posts. There is also fake 911 call audio and synthetic gunshot-detection sensor data.

In all, there are more than 60 emergency events in the data across eight hours of life in a simulated city, recorded with actors and actresses at a Department of Defense training facility in Indiana. Only teams associated with US businesses or universities may participate in the ASAPS challenge.

Garofolo, a senior adviser at NIST, has previously worked with the intelligence community and White House on projects analyzing multiple videofeeds. He led the effort to create the ASAPS data set, which he likened to producing a Hollywood movie. As part of the AI City Challenge workshop, Garofolo showed a snippet of video from the ASAPS data of people fleeing the scene of a shooting, pairing that footage with mock tweets.

Last year, he said the results of the competition showed the need to invest more in AI talent in the US. Emphasizing that he was speaking as an individual, he says the open sharing of knowledge is still important for the scientific community, along with the growth and development of expertise based in the US.

Originally published at Wired