Bone fragments discovered in a cave in central Germany indicate that our species ventured into the continent’s frigid higher latitudes more than 45,000 years ago.

In a remarkable revelation that reshapes the narrative of early Homo sapiens in Europe, bone fragments discovered in a cave in central Germany indicate that our species ventured into the continent’s frigid higher latitudes more than 45,000 years ago.

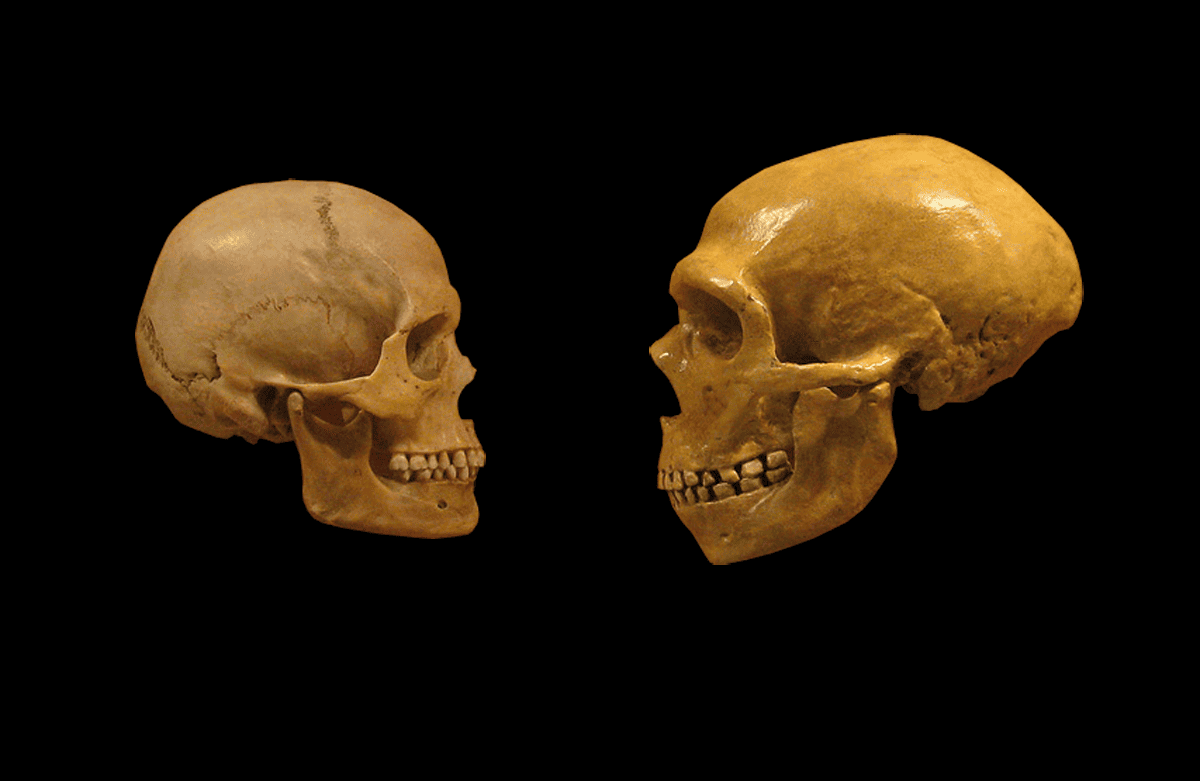

This groundbreaking finding, much earlier than previously known, challenges existing theories and sheds new light on the coexistence of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in a Europe still dominated by our ancient cousins.

A team of scientists, led by paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin from Collège de France in Paris, identified 13 Homo sapiens skeletal remains in the Ilsenhöhle cave, located beneath a medieval hilltop castle in Ranis, Germany. Through ancient DNA analysis, the researchers determined that these bone fragments date back up to 47,500 years, pushing back the timeline of Homo sapiens’ presence in northern central and northwestern Europe by several millennia.

Hublin stated, “These fragments are directly dated by radiocarbon and yielded well-preserved DNA of Homo sapiens.” This discovery challenges our understanding of how Homo sapiens migrated through Europe and their role in the extinction of Neanderthals, who disappeared around 40,000 years ago.

The research, presented in three studies published in the journals Nature and Nature Ecology & Evolution, indicates that the region was colder during this period than it is today, resembling the chilly steppe-tundra settings of present-day Siberia or Scandinavia. Despite originating in warmer Africa, Homo sapiens adapted swiftly to these frigid conditions, highlighting their remarkable ability to thrive in diverse environments.

The scientists concluded that small, mobile bands of hunter-gatherers utilized the cave sporadically while navigating a landscape populated by Ice Age mammals. The cave also served as a habitat for cave hyenas and cave bears during other periods.

Archaeologist Marcel Weiss of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg emphasized, “The site in Ranis was occupied during several short-term stays, and not as a huge camp site.” The bone fragments and stone artifacts discovered in the cave revealed a diet centered around hunting large mammals, including reindeer, horses, bison, and woolly rhinoceroses.

Zooarchaeologist Geoff Smith of the University of Kent, who led one of the studies, noted the significance of the dietary focus on large terrestrial game for both early Homo sapiens and late Neanderthals.

He commented, “However, we still need additional data points to more fully understand the role and impact of climate and incoming Homo sapiens groups in the eventual extinction of Neanderthals in Europe.”

The research also settled a longstanding debate about the origin of specific European stone artifacts attributed to the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician (LRJ) culture, including leaf-shaped stone blades suitable for spear tips. While many experts previously hypothesized that Neanderthals crafted these tools, their presence at the Ranis site without evidence of Neanderthals indicates that Homo sapiens were responsible for their creation.

Geoff Smith elaborated, “These blade points have been found from Poland and Czechia, over Germany and Belgium, into the British Isles, and we can now assume they most likely represent an early presence of Homo sapiens all over this northern region.”

The researchers identified the bones based on mitochondrial DNA, reflecting maternal heredity. Further analysis of nuclear DNA may provide additional insights, including potential interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals at Ranis.

The Ilsenhöhle cave was initially excavated in the 1930s, with bones and artifacts discovered. World War II interrupted the work, and it was not until 2016-2022 that researchers re-excavated the site, utilizing modern technology to identify the bones.

Weiss concluded, “The results for Ranis are amazing,” suggesting that similar evidence of early Homo sapiens presence may exist in other European sites from this time period. This groundbreaking discovery prompts a call for further exploration and reevaluation of our understanding of human evolution in Europe.