Despite the growing harm it does to human health, the energy and waste generated by health research contributes significantly to the climate crisis.

In the field of health research, adopting a number of sustainable practices could help it reduce its significant carbon footprint, according to a report commissioned by the funding organization Wellcome for medical research.

Despite the growing harm it does to human health, the energy and waste generated by health research contributes significantly to the climate crisis. According to a 2011 study1, one clinical trial may generate about 180 tonnes of carbon dioxide yearly, which is equal to the amount that 35 people in the UK emit.

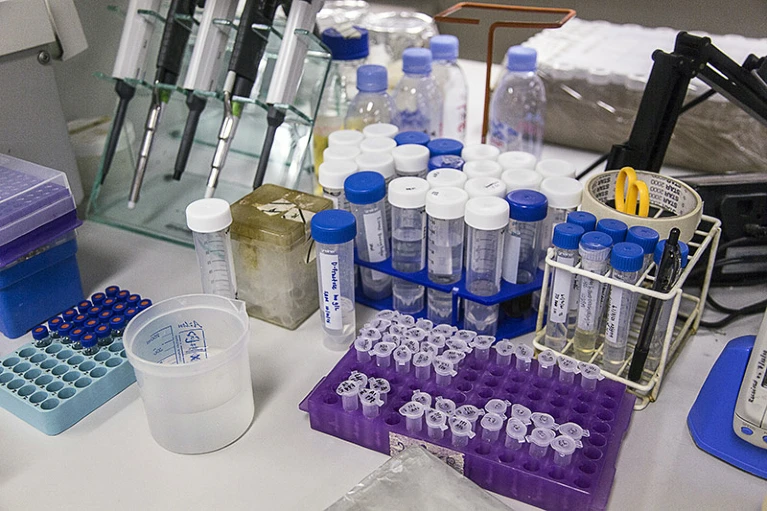

Many research in the life sciences need materials to be stored in refrigerators and freezers for extended periods of time, making cold storage one of the energy-intensive activities in labs. Another problem is plastic trash; in 2015, it was projected that 5.5 million tonnes worldwide, or about 2% of all plastic garbage, was created for laboratory purposes.

When it comes to health research and practice, “we kind of let a lot slide because we’re trying to help people’s health,” explains Talia Caplan, a research manager at Wellcome in London.

The Wellcome report, which was released on August 2nd, examined current initiatives by health researchers everywhere to cut back on energy and waste. It identified 146 sustainability initiatives, which it categorized into 8 types, including staff networks, campaigns, measurement tools and certification programmes.

As an illustration, consider Future Earth, a network of scientists operating on a worldwide scale that supports sustainability activities through its own programs as well as through collaborating with funders and increasing awareness among researchers.

The Laboratory Efficiency Assessment Framework (LEAF), a program that grants participating laboratories a gold, silver, or bronze certificate based on their sustainability level, is another. The approach decreased carbon dioxide emissions by 648 tonnes over a 2-year trial period at 23 research locations in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The impact of LEAF has already reached 85 institutions in 16 nations.

According to Imperial College London’s lab-efficiency resource consultant Allison Hunter, researchers are becoming more and more concerned with sustainability.

Wellcome study stated that individual scientists who are committed to the subject lead the majority of sustainability projects. Nearly every initiative mentioned in the report was voluntary. According to Hunter, resources and organization are still required even when people are prepared to invest in sustainable working methods.

She cites the fact that, for instance, there is no established method in Europe for determining which lab freezers are the most energy-efficient, making it difficult for scientists to estimate how much electricity they may be consuming and devise strategies to cut it without taking the time to measure their precise energy consumption. It will take some time to determine how much energy each piece of lab equipment consumes, she adds.

The paper urges organizations to promote sustainability projects more effectively, including universities, research publishers, and funders. A national concordat is being put together by UK funders with the intention of promoting efficient, long-lasting, and sustainable processes in the research sector.

According to Caplan, the study will influence Wellcome’s award recipients’ environmental sustainability strategy, which is anticipated to be released by the end of the year.

It’s a difficult challenge, according to Caplan, and it’s multifaceted. She hopes that the Wellcome report will serve as a springboard for the development of a larger evidence base of methods and procedures to aid in the shift to more environmentally friendly research.