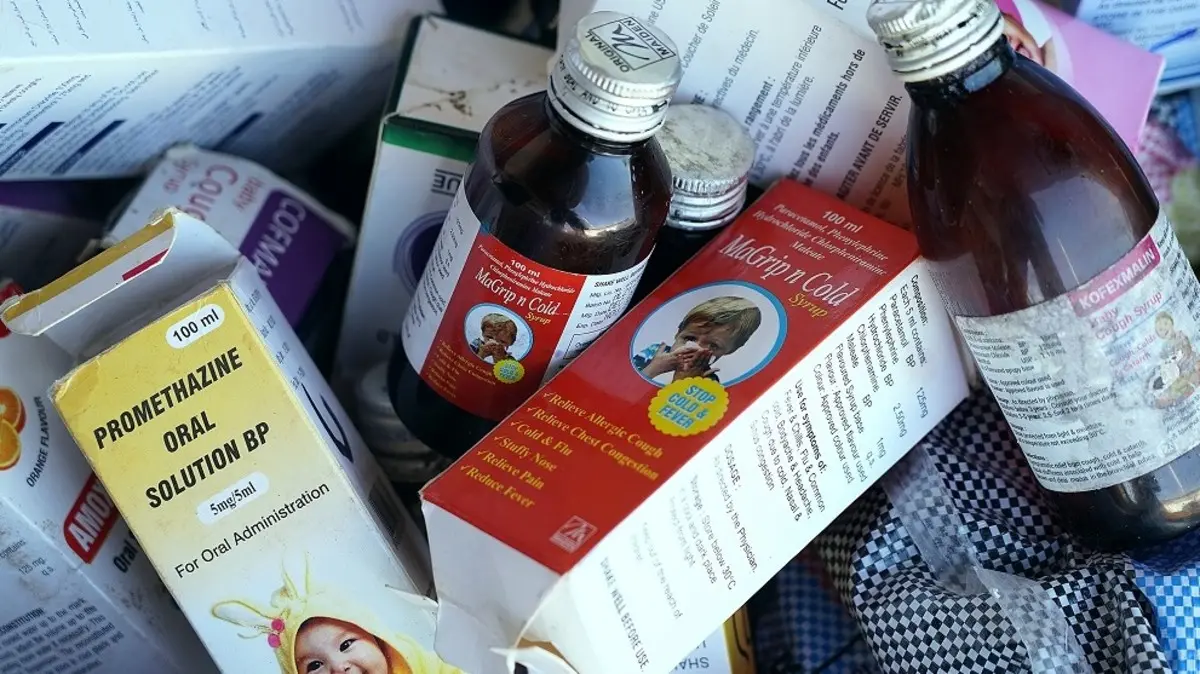

Lamin was one of the 70 Gambian children under age of five who died from severe kidney damage after consuming cough syrups produced by Maiden Pharmaceuticals.

Lamin, a 3-year-old, was one of the 70 Gambian children under the age of five who died from severe kidney damage after consuming cough syrups produced by the Indian company Maiden Pharmaceuticals.

The World Health Organization (WHO), which said it had discovered “unacceptable” levels of toxins in the medications, connected the fatalities to the syrups in October.

Following an examination, a Gambian parliamentary commission came to the same conclusion that the children’s use of the syrups was what caused the fatalities.

Both Maiden Pharmaceuticals and the Indian government have refuted this; in December, India said that tests conducted at home revealed the syrups to be in compliance with quality norms.

Amadou Camara, the head of the Gambian team that looked into the fatalities, vehemently disputes this finding.

“We have proof. We examined these medicines. He claims that the products, which were made by Maiden and were directly imported from India, “contained unacceptable levels of ethylene glycol and diethylene glycol.” Humans are poisonous to ethylene glycol and diethylene glycol, which when taken can be lethal.

The Gambia, one of the tiniest nations in Africa, faces a challenging scenario since it imports the majority of its medications from India. Some grieving parents claim they no longer trust pharmaceuticals produced in India.

Lamin Danso, who lost his nine-month-old baby, stated “I barely touch it when I read that a medicine is from India.”

But it’s doubtful that the reliance on Indian pharmaceuticals will diminish any time soon.

According to journalist Mustapha Darboe, “most chemists are still importing drugs from India because it’s much cheaper than importing drugs from America or Europe.”

The majority of the medical requirements of developing nations are met by India, which is the largest supplier of generic medications in the world. However, concerns about its manufacturing procedures and quality standards have been raised in light of claims that its drugs have contributed to tragedies like the one in The Gambia, as well as in other nations like Uzbekistan and the US.

“If you look at the tragedy and the alerts that the WHO has issued, so many nations are reconsidering. They frequently ask questions. It’s not really cozy. I refer to it as an anomaly.”

Udaya Bhaskar, director general of the Pharmaceuticals Export Promotion Council of India, calls it an expensive anomaly.

He claims that although incidences like those in The Gambia and Uzbekistan have “made a dent” on the reputation of the Indian pharmaceutical business, exports have not been affected.

In the fiscal year that ended in March 2023, India exported pharmaceuticals worth $25.4 billion (£20 billion), of which $3.6 billion went to nations in Africa. In the first quarter of the current fiscal year, Mr. Bhaskar notes, the nation has already exported pharmaceuticals worth more than $6 billion.

However, India has announced measures including making it mandatory for businesses to have samples of cough syrup tested at government-approved labs before exporting. Since July, The Gambia, which lacks drug testing facilities, has likewise made this a requirement for pharmaceuticals shipped from India.

India has also established timeframes for its pharmaceutical businesses to implement GMPs that adhere to WHO standards.

However, some Indian activists assert that the nation has historically maintained a “two-tier manufacturing system”.

Dinesh Thakur, a public health campaigner, asserts that “we try and use much more stringent standards for what we export to the US and Europe compared to drugs made for local consumption and exported to less regulated markets.”

Mr. Bhaskar disagrees, claiming that some African nations—the third-largest export market for India—have “robust” regulatory frameworks.

Following the disaster, a government study in the Gambia advised the creation of a quality control laboratory and urged the dismissal of two drug regulators. Billay G. Tunkara, the leader of the Gambian National Assembly, is aware of the rage felt by victims and other sections of society.

As the medical system struggled to handle fever cases and some parents were forced to evacuate their children to neighboring Senegal, parents believe that the health sector has not improved over the previous year.

The Gambian high court has received a lawsuit from the relatives of 19 children against the local health department and Maiden Pharmaceuticals. They claim that if necessary, they won’t hesitate to go before Indian and international courts as well.

Mr. Sagnia, a member of the organization, claims that the children’s deaths were caused by the government’s neglect.