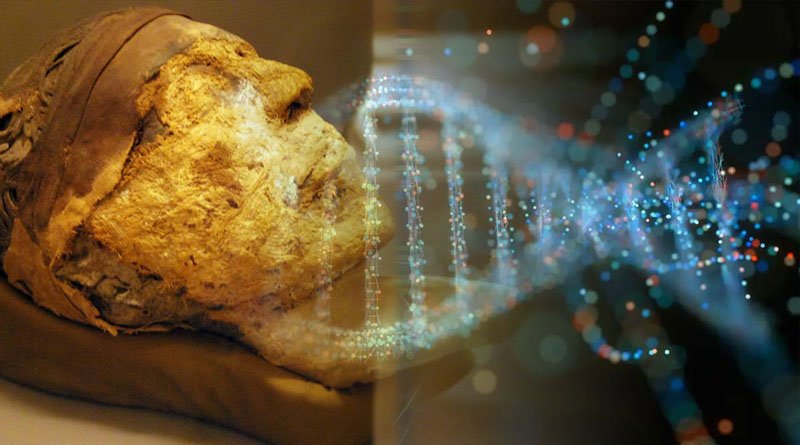

Scientists have come up with reliable ways to sequence and check DNA, and used Egyptian mummies to do the first successful genomic tests.

The problem, it was thought, is that Egyptian mummy DNA couldn’t be sequenced. But a group of international researchers, using unique methods, have overcome the barriers to do just that. They found that the ancient Egyptians were most closely related to the peoples of the Near East, particularly those from the Levant.

This is the Eastern Mediterranean, which today includes the countries of Turkey, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. The mummies used were from the New Kingdom and A later period, (a period later than the Middle Kingdom) when Egypt was under Roman rule.

Modern Egyptians share 8% of their genome with central Africans, far more than ancient ones. The study was led by archaeo-geneticist Johannes Krause, also of the Max Planck Institute. Historically, there’s been a problem finding intact DNA from ancient Egyptian mummies.

“The hot Egyptian climate, the high humidity levels in many tombs and some of the chemicals used in mummification techniques, contribute to DNA degradation and are thought to make the long-term survival of DNA in Egyptian mummies unlikely,” the study noted.

It was also thought that, even If genetic material were recovered, it may not be reliable. Despite this, Krause and colleagues have been able to introduce robust DNA sequencing and verification techniques, and completed the first successful genomic testing on ancient Egyptian mummies.

Each came from Abusir el-Meleq, an archaeological site situated along the Nile, 70 miles (115 km) south of Cairo. Some of the mummies in this cemetery show that they were devoted to the cult of Osiris, the green-skinned god of the afterlife.

First, the mitochondrial genomes from 90 of the mummies were taken. Krause and colleagues discovered that they could obtain the entire genomes from only three of the mummies. For this study, scientists took teeth, bone, and soft tissue samples. The teeth and bones offered the most DNA. They were safe because the embalming process kept the soft tissue from breaking down.

Researchers took these samples back to a lab in Germany. They began by sterilizing the room. Then they put the samples under UV radiation for an hour to sterilize them. From there, they were able to perform DNA sequencing.

Scientists also gathered data on Egyptian history and archaeological data of northern Africa, to give their discoveries some context. They wanted to know what changes had occurred over time. To find out, they compared the mummies’ genomes to that of 100 modern Egyptians and 125 Ethiopians. “For 1,300 years, we see complete genetic continuity,” Krause said.

The oldest mummy sequenced was from the New Kingdom, 1,388 BCE, when Egypt was at the height of its power and glory. The youngest was from 426 CE, when the country was ruled from Rome. The ability to acquire genomic data on ancient Egyptians is a dramatic achievement,

One limitation according to their report, “all our genetic data were obtained from a single site in Middle Egypt and may not be representative for all of ancient Egypt.” In southern Egypt they say, the genetic makeup of the people may have been different, being closer to the interior of the continent.

Researchers in future want to determine exactly when sub-Saharan African genes seeped into the Egyptian genome and why. They’ll also want to know where ancient Egyptians themselves came from. To do so, they’ll have to identify older DNA from, as Krause said, “back further in time, in prehistory.”

Researchers showed that they could get reliable DNA from mummies, despite the harsh climate and damaging ways they were preserved. They did this by using high-throughput DNA sequencing and cutting-edge authentication techniques.