The A-74 icebergs, which is about twice the size of Toronto, recently crashed into part of Antarctica, in what the European Space Agency (ESA) describes as a ‘minor impact.’

By Sharon Lindores

It was a near-miss of gigantic proportions.

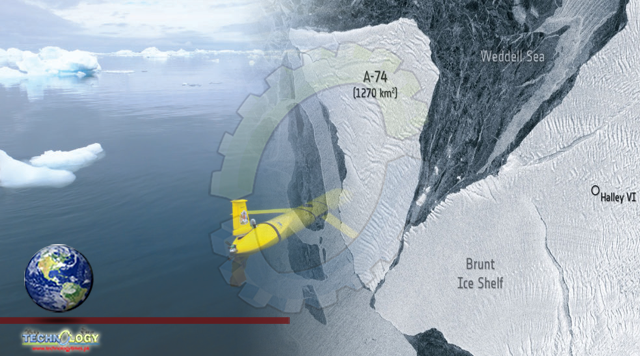

The A-74 iceberg, which is about twice the size of Toronto, recently crashed into part of Antarctica, in what the European Space Agency (ESA) describes as a ‘minor impact.’

If the collision had been more severe, another huge iceberg could have calved, or broken off of, the Brunt Ice Shelf on the western coast of the continent.

“The nose-shaped piece of the ice shelf, which is even larger than A-74 remains connected to the Brunt Ice Shelf, but barely,” Mark Drinkwater, an ESA geophysicist, said in a report dated Aug. 20. “If the berg had collided more violently with this piece, it could have accelerated the fracture of the remaining ice bridge, causing it to break away.”

The A-74 iceberg, which at 1,270 square kilometres is one of the largest in the world, originally split from the ice shelf in February and had been drifting nearby until easterly winds caused it to shift its course from Aug. 9 to Aug. 18.

The Brunt Ice Shelf was home to the British Antarctic Survey’s Halley VI Research station until 2017, when it was deemed unsafe. The team then moved their station about 20 kilometres away from Chasm 1, a large crack running northwards from the southernmost part of the ice shelf.

The ESA plans to continue to monitor the situation using Sentinel satellite imagery.

They aren’t the only ones watching.

David Long and his students run the Antarctic Icebergs Tracking Database (AITD) at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. They’re tracking 51 active Antarctic icebergs.

“Ice in Antarctica is a bellwether for global climate change,” Long said by email on Thursday. “As the oceans warm, the major floating ice sheets and glaciers melt from beneath and become unstable. This can lead to their breakup and the rapid release of land glacial ice stored behind them. This release will cause sea levels around the world to rise.”

While the calving of the Brunt Ice Shelf may allow the land glaciers to flow more rapidly to the sea and increase the global sea level, the minor incident with theA-74 iceberg is not a particular concern for the area, he said.

Scheridan Cloward, the AITD’s lead data analyst, is currently in charge of the real-time tracking of A-74. She said it’s following the polar current around Antarctica, which is to be expected.

“A-74 is in the area of the Weddell Sea, which we lovingly call ‘Iceberg Alley,’ as the combination of the polar currents and the Antarctic Peninsula create a thoroughfare for icebergs to pick up speed and make their way out towards open ocean,” she said by email on Thursday.

“The brief touch with the other point of the Brunt Ice Shelf is the impressive part,” Cloward said. “The fact that A-74 barely touched the other ice shelf without causing breakage or calving is notable. In contrast, D-28 collided with an ice shelf back in June of this year and caused five new icebergs to calve.”

The A-74 iceberg is expected to continue moving along the coast and to eventually go out to the Wendell Sea, although it’s not known how long the process will take, Cloward said.

Karen Alley, an assistant professor with the University of Manitoba’s Department of Environment and Geography in Winnipeg, said the calving of a large iceberg doesn’t mean the ice shelf itself is in danger of collapsing.

“The Brunt Ice Shelf is not rapidly thinning due to ocean or atmospheric warming, and while it normally loses a lot of mass to calving, that mass is replaced by ice flow from the continent at about the same rate as it breaks off,” Alley said by email on Thursday.

Glaciers and ice shelves that reach the ocean all calve periodically, but large calving events are rare and so it can be difficult to tell if they are a sign of change or normal behaviour, she said.

There aren’t any massive ice shelves in North America that are comparable to the Brunt Ice Shelf. However, many glaciers in Canada, Greenland and other parts of the Arctic do release smaller icebergs.

“These icebergs can be a navigational hazard, so it’s important to monitor their movements and understand the calving processes that create them in order to predict future iceberg changes in a warming Arctic,” Alley said.

“Many parts of Antarctica are melting and retreating rapidly, making the Antarctic Ice Sheet the largest concern for sea-level rise over the next few centuries,” Alley said. “The region where the Brunt Ice Shelf is located is a fairly stable part of Antarctica, making it likely that large calving events there are not of global concern.”

Originally published at Ctv news