A Chinese team studying “internal waves” so strong they can sink submarines in the Andaman Sea say they have developed a computer model to predict when and where the worst ones are likely to happen.

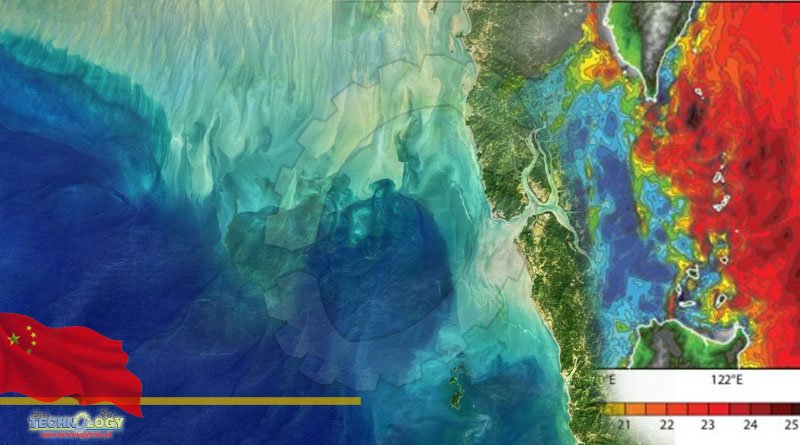

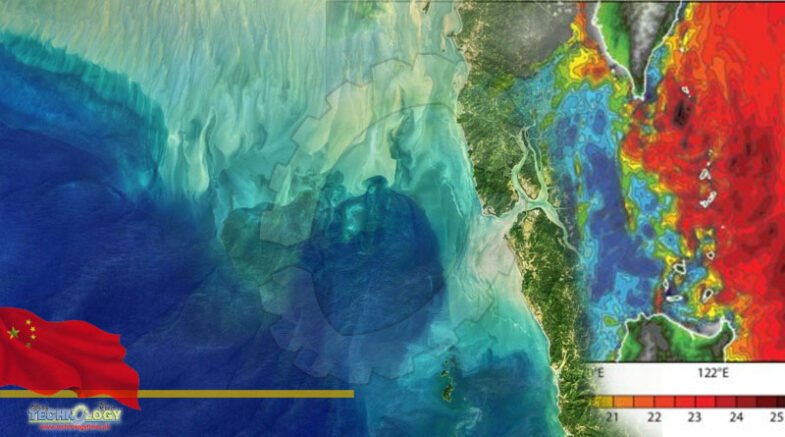

They focused on a particular area of the sea, where some of the world’s largest internal waves – or sudden changes in ocean density – occur, near the western end of the Strait of Malacca.

The researchers from the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Guangzhou set out to understand how the internal waves formed and developed, a process they said was more complex in the Andaman Sea than elsewhere.

This understanding could potentially help to improve submarine safety and combat capabilities like communication, target tracking and torpedo strikes.

The team found that some initial waves started from the southeastern shores of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands that separate the sea from the Indian Ocean, according to their paper published in Chinese journal Scientia Sinica Terrae on Monday.

These strong flows became internal waves after travelling east then bouncing back once they hit a steep hill on the sea floor, Dreadnought Bank, making the incoming waves even stronger, the researchers said. They formed deep pockets of low-density water that look much like a waterfall and could in some cases become over 100 metres (328ft) high – or twice the height of Niagara Falls.

If one of them suddenly hit a submarine it could drag it down below its operating depth and sink it. But the phenomenon is not just dangerous for submarines.

“Internal solitary waves through Computer Model [a particularly extreme type of internal wave] can have a big impact on the marine environment,” the team led by marine scientist Cai Shuqun wrote in the peer-reviewed paper.

“The numerical simulation at present only reveals part of the full picture,” they said.

Self-powered soft robot developed by Chinese scientists reaches world’s deepest point .Marine scientists only discovered that internal waves were caused by significant disturbances from the deep in the 1960s, though mysterious ripples on the ocean surface during calm conditions have been observed by sailors since ancient times.

In the Andaman Sea region, complex underwater landscapes make it harder for researchers to study the phenomenon. The floor of the Indian Ocean rises by nearly 3,000 metres to the west of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, then drops by more than 1,000 metres to the east. The terrain and currents are challenging, with numerous ridges, reefs and banks created by volcanoes and earthquakes.

A key question for the Chinese researchers was where did the internal waves in the Andaman Sea – some of them hundreds of kilometres long – come from. After analysing masses of data, they concluded that the most likely source was the southern tip of the Andaman archipelago and developed a computer model to test the theory.

The model estimated that the biggest downward currents occurred at locations in the middle of the Andaman Sea. So in those places, it could predict when it would be safest for a submarine to pass – during diurnal tides. That is when there is one high tide and one low tide in a day, and the internal waves would be much smaller.

More than half of China’s foreign trade passes nearby, through the busy Strait of Malacca, and while the underwater disturbances have little impact on ships on the ocean surface, Chinese naval activity has increased in the area in recent years, including to protect the country’s merchant vessels from pirate attacks.

China is also concerned that its neighbour India – whose exclusive economic zone covers a large part of the Andaman Sea – could cut off its most important trade route as their relationship deteriorates over a long-running border dispute and geopolitical rivalry in the region.

Chinese marine scientists have been studying internal waves for decades thanks to increased funding from the government, but the Andaman Sea only recently became a research focus. In the past few years the country has sent survey vessels to the sea and planted underwater sensors there to collect data for internal wave analysis and other research, according to openly available information.

Source SCMP