A startup called Spatial is unveiling its first suite of products today, focused on creating audio experiences that are immersive, interactive, and automatically generated.

A startup called Spatial is unveiling its first suite of products today, focused on creating audio experiences that are immersive, interactive, and automatically generated. The products themselves are a little complicated to explain, but the result is simple: ambient and interactive audio for public spaces that’s easy to create and more dynamic than the usual tracks.

Although Spatial has a consumer offering, the most likely customers are going to be businesses. Think hotels that want a different audio experience in their lobby, theme parks that want to develop audio for their spaces faster, brand activations, or AR experiences (National Geographic is an investor). Think about how corny the canned audio at the zoo often is; Spatial wants to fix that.

In one demo a couple of weeks ago, I sat in a room and heard the sounds of a forest all around me, with birds chirping in one spot and then moving to another — until a dragon flew overhead and scared them all away for a little while.

That’s frankly nothing special: audio positioned in space is simple. What’s complex is the engine that created all of that audio. Spatial’s goal is to make designing custom sound for a space easy and also to make that sound happen generatively instead of on a loop or a track. There are three main pieces to it.

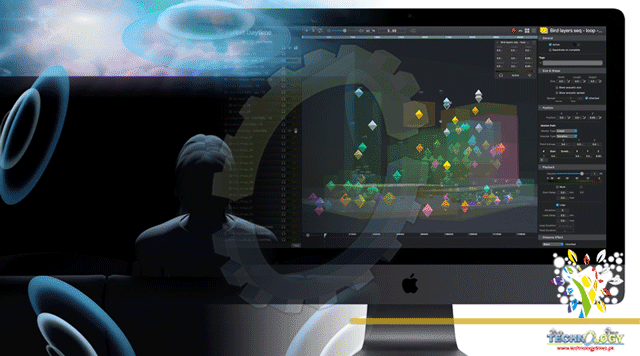

First, there’s Spatial Studio, a Mac app that’s a sort of unholy melding of Logic and Unreal Engine. It defines a 3D space where users can place audio objects – either sounds they’ve created themselves or pulled from Spatial’s library. Users can even pipe in live audio as an object – say, if they want to bring the sound of the nearby ocean up into the lobby or just run a Sonos stream.

What’s special about Spatial is that those audio objects have behaviors. A bird might move along a predetermined track (with some randomness so it doesn’t get boring) or an ocean tide might appear at certain times of day, for example. Those audio objects might also react — either to each other or to something that happens in the real space.

The second part of Spatial’s system is turning all those dynamic audio objects into actual sound that you can hear in a space. For that, it uses Mac minis (or, for corporate customers, Linux) to run a real-time audio engine called Spatial Reality. It will take inputs from various sensors if need be, or simply let the little audio world run its course — and since the things in that little audio world have different behaviors, it will sound different all of the time. Spatial has also created an iPhone app for more direct interaction.

You’d think the third part is the speakers, but that’s actually Spatial’s third trick: it can work with any speaker setup. Spatial’s engine serves as an abstraction layer that is aware of the speakers’ position in the room and automatically adjusts the sound to ensure correct 3D positioning of the audio. Instead of a strict set of placement rules, Spatial can work with what you’ve got.

Michael Plitkins, one of the cofounders, tells me that fundamentally he believes that laying down audio on a static track is backwards. It’s better, he says, to let the computers figure it out in real time based on what they know about the speaker system. As the product stands right now, Spatial isn’t bothering with any real-time tuning to the audio in the room. It will work with any speaker setup, but users will need to program in what they have in the Spatial Studio app.

At the start, Spatial’s main competition is some combination of Muzak for public spaces and whatever custom tools Disney Imagineers use for the audio in their theme parks. It may appeal to some hobbyists too — part of the inspiration for the company was Plitkins’ desire to create a soundscape in his own back yard. I had a demo of that space too, complete with cave sounds under the deck so authentic it was eerie.

Whomever the customers end up being, it probably won’t be an easy sell. (And launching a product meant mainly for public spaces while a pandemic is still on is another challenge.) Dynamically created rain and birdsong doesn’t sound any different from a static audio track if you only listen for a couple minutes.

But during a long interview in a conference room where the team explained the ins and outs of their product, they turned off the cabin in the woods-themed audio that had been gently playing the whole time. The silence was weirdly stressful, the way conference rooms usually are.

Originally Published at The Verge